My first visit to Albania was earlier this year in late September when I visited the northern Albanian town of Shkoder en route towards Montenegro after having spent a week in neighbouring Kosovo. Visiting the rest of the country wasn’t on the agenda on that trip but I vowed to return to Albania later in the year. Since the beginning of November I had been based in Athens for almost three weeks. Yet I made sure that I would return to Albania before the end of this trip.

From the northern Greek town of Ioannina, I took an early afternoon bus directly to the southern Albanian mountain town of Gjirokaster. I was the only tourist on the bus. Ioannina is a mountain town located on a plateau of around 500 meters. The entire sky was heavy with thick low lying clouds and I was wearing my warmest garments. During the two hour bus ride we drive through some awesomely stunning mountain landscape. There is no heating on the bus and my feet are turning to ice. The border crossing feels like its located at the same altitude as La Paz in Bolivia. On the Greek side we all have to get off the bus and I make an inward groaning sound. Uniquely for border crossings, the Greek border official is full energy and excellent humour. His English is impeccable…‘So Mr Nicholas Alexander, what the hell are you doing on the Greek-Albanian border?’ When we approach the Albanian side I feel relieved when we don’t have to disembark the bus. Instead the bus driver takes all our passports to give to the Albanian border official before handing them back to us.

By Lake Pamvotis in the northern Greek town of Ioannina

On arrival in Gjirokaster, the bus stops on the side of the main town boulevard, Bulevardi 18 Shtatori. Multiple red Albanian flags line the middle of the boulevard. I establish my bearings towards my guesthouse via Google Maps. With hindsight, it would have taken an age to find my place without all this digital cutting edge technology at my disposal. From the boulevard, I walk up multiple ascending narrow stone paths. As I get closer to my destination, the older part of town with its old historic Ottoman style houses (some splendidly dilapidated) slowly reveals itself to me. I wish I were wearing my hi tech Merrel brand boots with their tough Vibram grip. My trendy hipster Vans shoes are not made for walking these jagged stone paths. As I walk further up one of the paths, a young man on a donkey with a small cart attached to it passes me by.

Google Maps is on my side and eventually I reach my final destination, Mele Guesthouse, or at least I think I have? An elderly couple greet me at the gates and take me inside their house. I ask them for the whereabouts of Mele, but neither of them speak a lick of English. We sit down on the sofa in the living room and the lady goes to the kitchen and returns with a tray carrying a bowl of sweats and an oversized shot glass of raki. With weather as cold as this, the raki is like a hot woodfire stove in my belly. I am also presented with a photo album of the couple with two of their children, a son and a daughter, in Venice. I assume that the daughter is Mele. After some time, a man in his late 30s/early 40s appears. I have a giant lemon sweet drop in my mouth disabling me from speaking clearly. Mele, I learn, is the surname of the man who’s name is Edmond. He speaks excellent English and I follow him to his house next door where my room is located. There is a balcony by my room with a tremendous view over the rest of the city and of the dramatic wide snow capped mountain symbolic of this town. My room is not warm but Edmond tells me to use the air conditioning unit on the wall, which doubles up as a radiator during this time of year. Edmond and I sit on the sofa in the heated living room. He makes me a delicious and warm organic tea and mentions that he once lived in Milton Keynes for two years back in 2005. Nowadays he works as a metal welder in town and lives in the house with his partner and their adorable young kid.

I spend the remainder of the afternoon walking around the old town. I need to withdraw some local cash so I head back towards the new part of town where I originally arrived. Instead of the arduous multiple narrow paths route I earlier in the day, I find a descending stone paved road leading directly into that part of town. After withdrawing my cash, I enter a bakery and order a slice of cheese and spinach pie and a wedge of halva cake. It all comes to about one Euro in the local Leks currency. That same purchase down the road in Ioannina would have cost me three times more. I am served by a young woman of about 20 who speaks passable English. She is so lovely and kindhearted, and admits to me that she cherishes all the opportunities to practice her English. Her name is Ada and she’s a student at a local university.

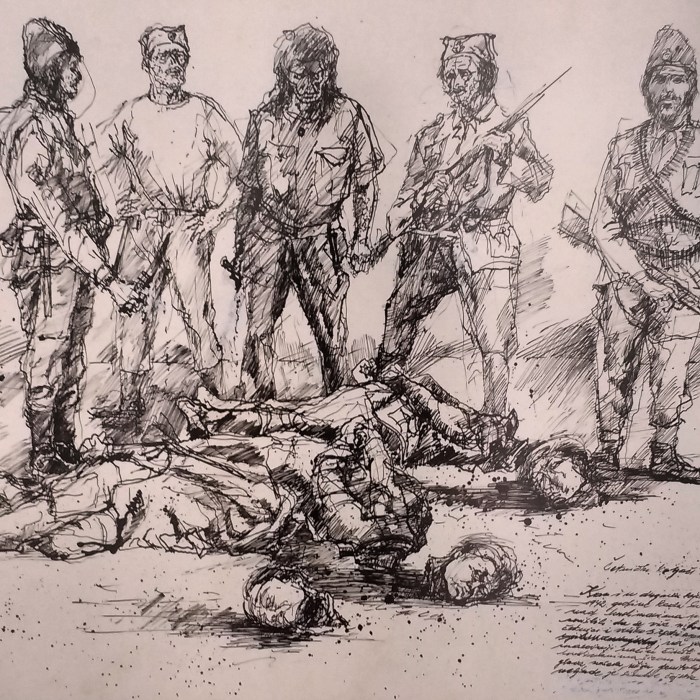

When I return to the old part of town, I try to find Taverna Kuka, a restaurant recommended to me by Edmond. The wooden taverna is aesthetically very tasteful and well heated. On one wall, there are several framed pencil sketches of assorted areas of the old town by a local artist. My first choice, the moussaka, is unavailable so I settle on a plate of qifqi, a local ball-shaped delicacy made from rice, dhjozme, egg, salt, pepper and milk.

Taverna Kuka

A plate of qifqi and meatballs

At night the temperature drops below zero. The air-con is humming away converted ice cold air into warm air. It’s a cumbersome and electricity wasting process and nothing beats a radiator, whether portable or nailed to the wall. Entering my private bathroom, which is unheated I must add, is like accidentally wading into a winter in Vorkuta. I pee and brush my teeth with haste before exiting back into a warmer vacuum. Edmond has kindly provided me with enough blankets to prevent the entire population of Gjirokaster from developing hypothermia.

When I wake up at 7am the next day, I roll up the shutters covering the sliding balcony glass doors. I am rewarded with a pristine blue day. The wide mountain and town skyline are majestic. I am served a decent breakfast of bacon, eggs, bread, sweet pickles and a Nutella crêpe. Wolfing down my breakfast, I tell myself Carpe fucking Diem. I am going to live today like its one of my last. I have the energy of James Brown, sans angel dust.

View of Gjirokaster from the balcony of my guesthouse room

Breakfast on the balcony

The first site in town I visit is the former childhood home of the Albanian president-for-life Communist dictator Enver Hoxha. Hoxha ruled the country for over 40 years from 1944 until his death in 1985. During his rule he cut off the country from most of the world. Albanian civilians were not allowed to leave and his regime tortured and killed thousands. Albania was comparable to Fidel Castro’s Cuba or present day North Korea during this period.

Enver Hoxha

Hoxha’s childhood home is an old Ottoman style house over 100 years old, which has been converted into the town’s ethnographic museum. Most of the wooden features and designs of the house appear to be original and well preserved. In contrast to this, many of the old historic Ottoman style houses dotted around the old town look neglected and in a decaying state of disrepair. In the vestibule of the first floor of the house, there is a small corner table with two black and white photographs of Hoxha resting on the wall. The living and guest rooms of the house are furnished with long sofas, antique carpets, intricate Ottoman style wooden reliefs on the wall and also some artillery pieces like the two rifles in one of the rooms.

The childhood home of Enver Hoxha now the Ethnographic museum in Gjirokaster

Photographs from inside the Ethnographic museum in Gjirokaster

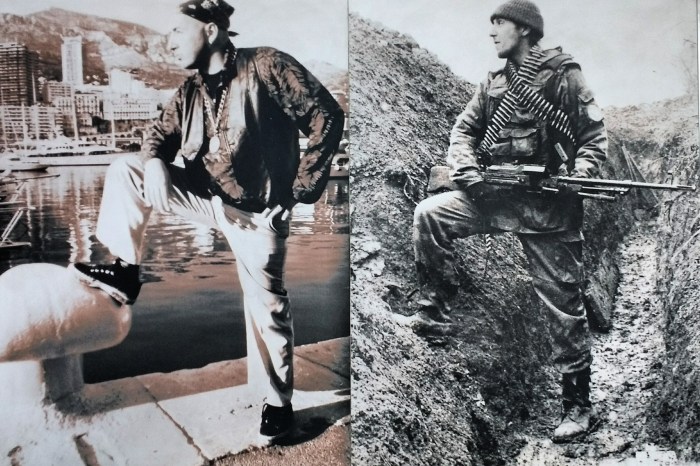

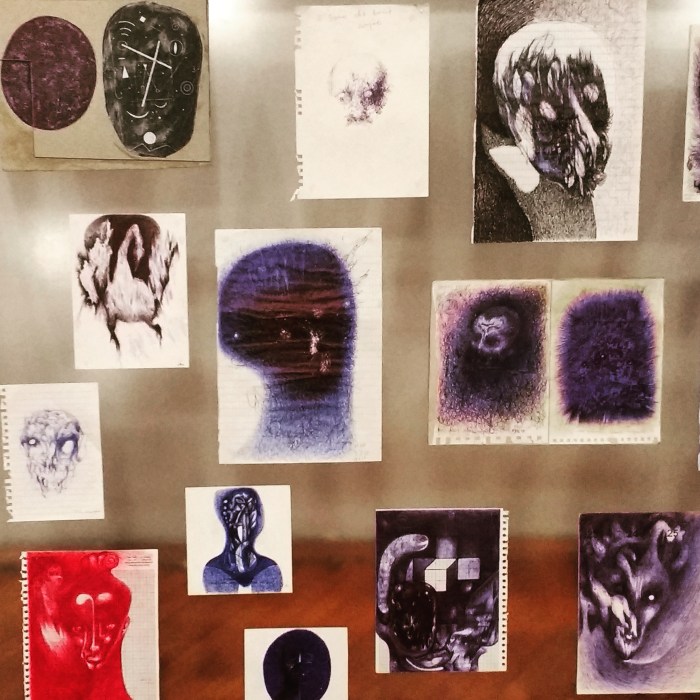

Another figure to come from Gjirokaster is one of Albania’s best known literary figures, Ismail Kadare. I visit his former home, which has been reconstructed after a fire in the 1990s destroyed the original structure and features. It is used as an exhibition space today and when I visited there were a number of Expressionist style oil paintings by a local artist dotted around the home. In one room there is a small table with black and white photographs of Ismail as a young boy, some books, the hat he wore whilst he was a journalist in Vietnam during the war and a certificate honouring Kadare for winning the Jerusalem Prize for the Freedom of the Individual in Society of 2015.

Inside the former home of Albanian writer Ismail Kadare

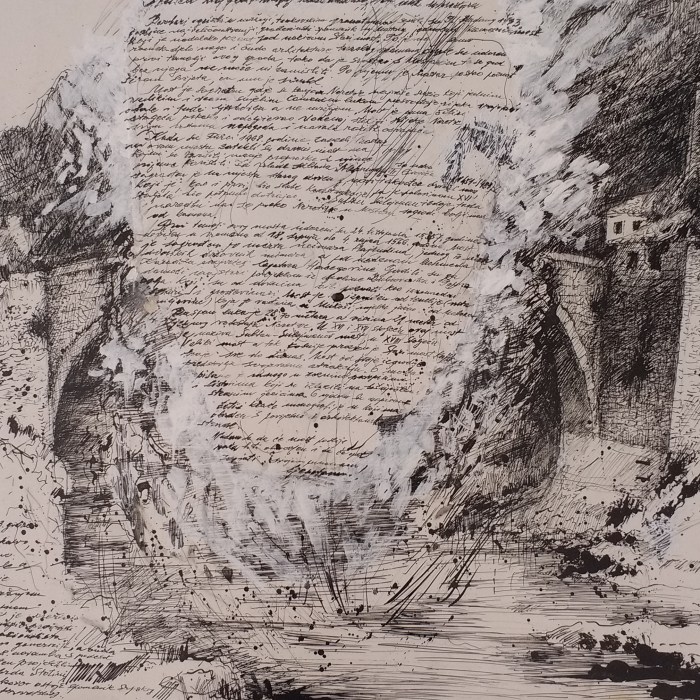

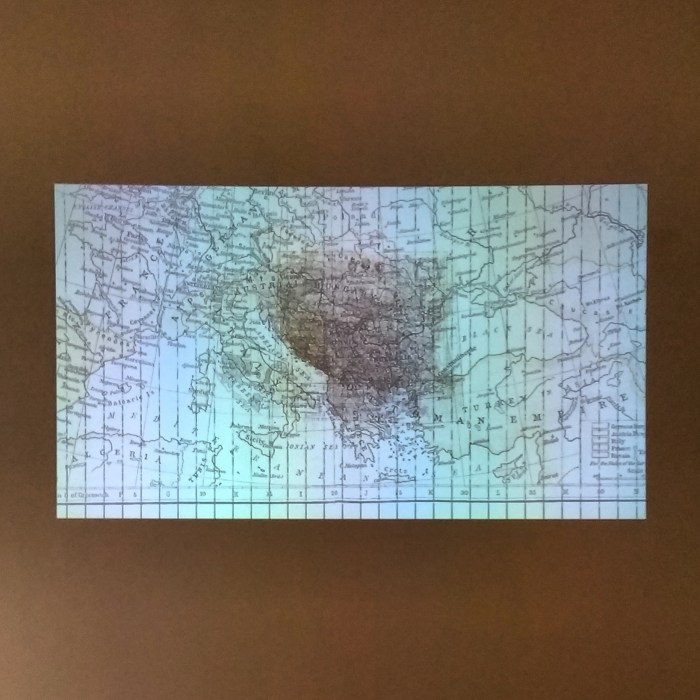

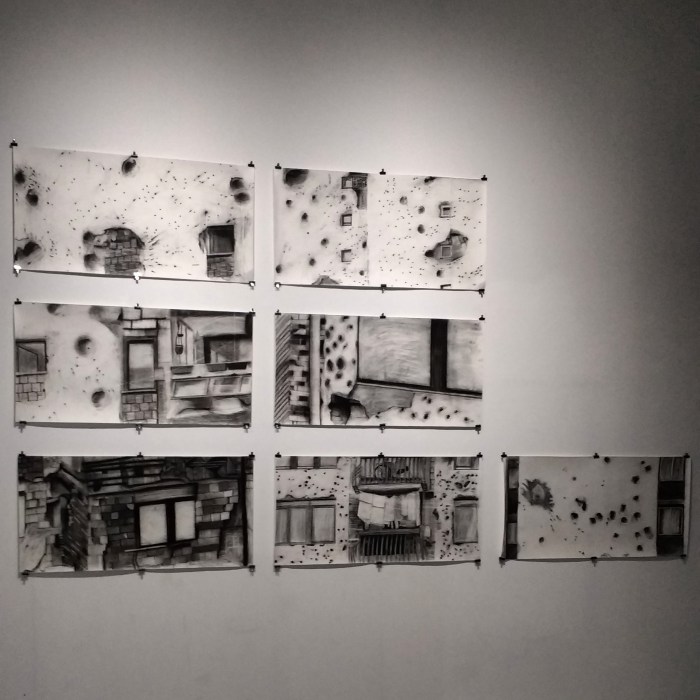

Afterwards I head to the enormous hilltop fortress of Gjirokastra. Just before I walk up the steps towards the fortress, I get lost walking up some of the mazes of surrounding stone pathways. The higher I climb the more awesome a view I have of the fortress and the old bazaar. The wide snow capped mountain in the distance, visible from my balcony, augments the beauty, rawness and authenticity of this historic slice of Albania. When I enter inside the fortress, I arrive at an area with great tall multiple stone arches and a collection of artillery dating back to the Second World War. Most of these weapons belonged to German and Italian forces, which occupied Albania during that time. The fortress is also home to the Museum of Gjirokaster. The museum contains numerous displays and information documenting the history of the city from as far back as pre-historic times. Of most interest to me is the period of history starting from when the Ottoman Empire conquered the Balkans region. In 1417, Gjirokaster became part of this empire. Since that time the town grew immensely and Islam became the dominant religion, although the Ottomans were tolerant towards the existing Christian communities.

Fortress of Gjirokaster

The artillery gallery inside the fortress

By the time of the 18th and 19th centuries, Gjirokaster was an important administrative centre for the empire. It was around this time in 1811 when the city was captured by Ali Pasha of Ioannina, the last town I visited before I arrived in Gjirokaster. To say that Pasha was a formidable ruler would be an understatement. From the modest bits and pieces I’ve read up on him, he strikes me as the quintessential larger than life colonial despot; an intimidating and nightmarish version of Louis XIV of France on an eternal cocaine comedown. Or more generously, a PG certificate Ghenghis Khan. Lord Byron famously visited his court in the walled Turkish Kastro in Ioannina in 1809 and had conflicting feelings about the man. On one hand he was impressed by the ruler’s cultural refinement and the opulence of his court yet he was shocked by his propensity for off the charts barbarism as he wrote in a letter to his mother, ‘His Highness is a remorseless tyrant, guilty of the most horrible cruelties, very brave, so good a general that they call him the Mahometan Buonaparte…but as barbarous as he is successful, roasting rebels, etc, etc..’ An example of his brutality include tales of drowning people who rubbed him up the wrong way by bundling them into sacks loaded with stones and then tying up the sacks before proceeding to drop them in Lake Pamvotis below the walls of his court. I recalled walking by that lake close to the Kastro and former court of Ali one cold and overcast day on my way to the bus terminal hellbent on getting to Albania. All the leaves on the trees by the lake were golden autumn brown. Ignorance is bliss and all I can remember is being struck by the beauty of the nature of my surroundings. Ali Pacha of Ioannina back then was just a name and I knew almost nothing about the man and the history of the town I was passing through.

Ali Pasha

But back to Gjirokaster before I digress any further. The origins of the fortress date back as far as the 12th century but it wasn’t until the time when Ali Pasha first seized the town that major changes occurred. He instigated an enormous building project to expand the fortress with the help of his chief architect, Petro Korçari. His expansion project included new fortifications, the clock tower and an aqueduct to transport water from a mountain spring to fill the huge cisterns in the castle. The fortress was large enough to house up to 5000 soldiers along with their weapons and other supplies. An arsenal of 85 assorted British made state of the art arms were added to further protect the fortress from invasions. Not surprisingly, during Ali Pasha’s rule, the fortress never came under attack.

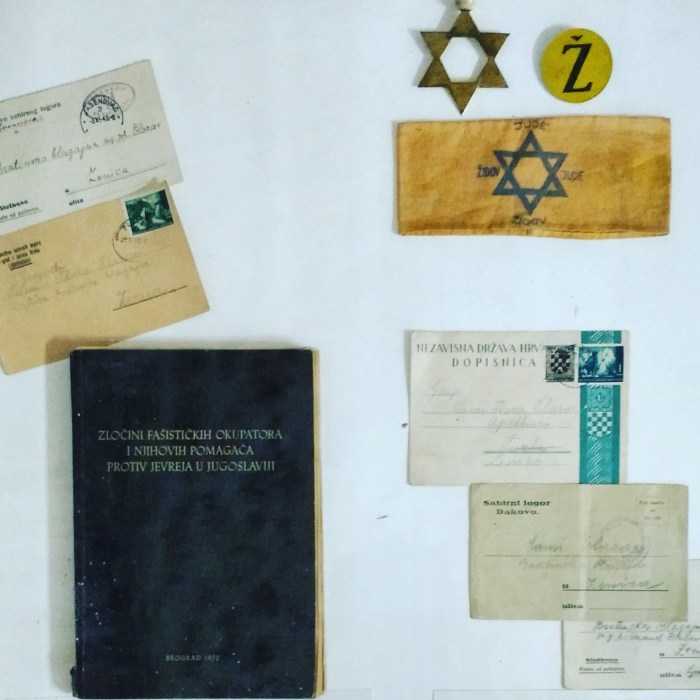

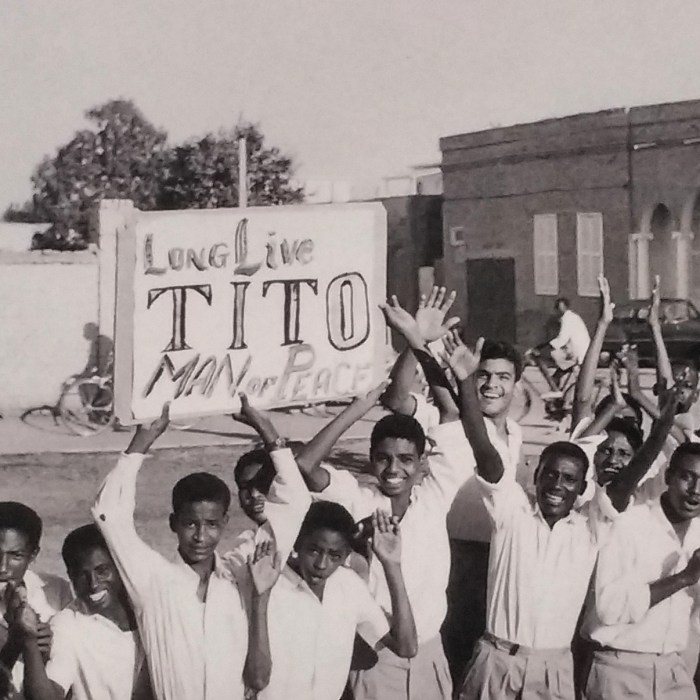

Some other interesting things I discovered in the museum about Gjirokaster include how fond the English landscape painter and poet, Edward Lear, was of the town. He visited two times in 1848 and 1859 on his travels through the Balkans. There are two black and white photographs which ignite my curiosity. One is a photograph of the old town from 1925 and the other is a photograph of locals hacking away with a hammer at the large town statue of Enver Hoxha after the fall of Communist rule in 1990. Although Gjirokaster is his place of birth and the town where he grew up, during his 41 year rule of Albania from 1944 until his death in 1985, he only visited his hometown a few times. There is also a display of miscellaneous ephemera from the Communist era such as political propaganda papers and identity documents.

Painting of the fortress and the connecting aqueduct by the 19th century English painter and poet Edward Lear

The old town of Gjirokaster in 1925

Locals posing by and hacking away at the statue of Enver Hoxha in Gjirokaster after the fall of Communism in the early 1990s

Objects and ephemera from the Communist period

From the top of the fortress, one is rewarded with a monumental view of the famous wide mountain of Gjirokaster. Ali Pasha’s clock tower is located near the end beneath the backdrop of the mountain. Elsewhere there is a large metallic dome shaped structure over a circular stage. This is where the National Folk Festival is held every four or five years.

The Ali Pasha built clock tower of the fortress of Gjirokaster

With less than a couple of hours remaining of light on these preciously short days, I make my way towards Zekate House; a grand Ottoman era house and probably the most spectacular of all the grand houses in Gjirokaster. It was built between 1811-12 and was a gift from Ali Pasha to Beqir Zeko (whom the house is named after) who built the house for him. It is located on a high slope over looking the rest of the old town. The view from the top of the house over Gjirokaster is just as epic as the view from the top of the fortress. The house is incredibly well preserved with almost all of its original features. One of the guest rooms comprises of ornate Ottoman style art on the walls and a beautifully designed wooden ceiling in the same style. Some of the windows feature multicoloured glass pains.

The grand Ottoman era Ali Pasha constructed Zekate House

One of the guest rooms inside Zekate House

In the evening the temperature drops dramatically hovering around the -5/-6 Celsius mark. Even with the aircon unit going into overdrive to pump warm air it isn’t enough and dispite having all the blankets in the world, I consider sleeping in my clothes. All this aside, the guesthouse is very homely and Edmond and his partner did their very best to make my stay as pleasant as possible. Edmond organises his friend to collect me after breakfast the next day to drive me to a part of town from where my bus to the town of Berat, further north of the country before the capital of Tirana, would depart. His friend arrives in a black Mercedes Benz parked at the bottom of the path leading up to Edmond’s home. With hindsight I am glad I opted for a cab. I most likely would have got hopeless lost had I gone it alone. Edmond’s friend doesn’t speak a word of English and the young lady at the office of one of the bus companies is not much better. Fortunately I have my phone so I give Edmond a call and he communicates with both his friend and the lady. I later learn that the bus to Berat will be arriving at a later time. Two minutes later I am bundled into a white mini van destined for the Albanian town of Lushnjë from where I have to catch another bus to Berat. When I enter the van it is close to full capacity and I find a seat in the row of seats right at the back of the van.

Leaving Gjirokaster, we slowly descend to a lower plateau and the temperature becomes noticeably milder, but I am still wrapped up. There is no heating system in the van. Before we reach Lushnjë, the bus driver points to a sign indicating the direction to Berat. The driver speaks zero English yet he directs his hand pointing frantically to a small bay area by the connecting road. I assume a Berat bound bus will be stopping there? Still I am not sure so before disembarking the bus I make an impromptu call out to all the passengers on the bus beginning by asking whether anyone speaks English? Thankfully a young lady with dyed platinum hair comes to the rescue and is able to confirm in modest English that I need to go to the bay area the bus driver keeps relentlessly pointing at. I say the Albanian word for thank you, faliminderit, about a dozen times putting my right hand to my heart.

Like some travelling 1930s Mississippi Delta Bluesman, I trudge with all my stuff over to the other road and the small bay area. Within five minutes a Berat bound battered furgon appears and I nudge myself inside with my suitcase. I am dropped off somewhere outside of Berat from where I board a local bus to the centre. The ticket seller on the bus asks me in broken English what football team I support? I am not a football man but I tell him Tottenham. He looks at me and smiles, exposing a set of truly disgusting broken and jagged nicotine stained teeth; a sight so disturbing I conclude this is someone not suitable to be around young kids. ‘Chelsea!!!’ he howls at me in a voice so piercingly loud all the other passengers stop what they are doing.

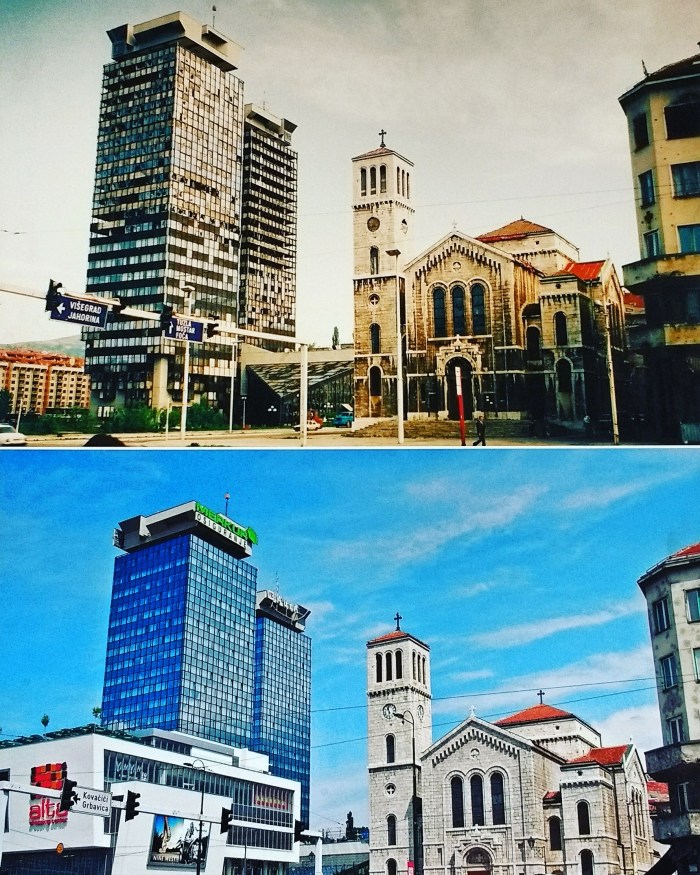

Berat

From the centre of town I disembark with my suitcase and walk, via trusty Google Maps, to my guesthouse located in a quiet and desolate location on the margins of the centre of town. It is a small newly built bungalow home with a few rooms. The outside of the house is no great shakes, but the few rooms inside are all in immaculate condition. In spite of this the rooms are very cold and even the air con unit doubling up as a heater doesn’t sufficiently heat up the room. The floor is cold as ice and the bathroom is one big freezer with a wooden door. The owners, an old Albanian couple, have a heart of gold though and the price per night is ridiculously cheap and good value. Too good in fact, especially if you consider that the price included a very generous breakfast of assorted slices of ham, jams, bread, feta cheese slabs and cut pieces of cucumber and tomato. Yet the cold temperature of my room means I sadly have to move on to another place the following day. The second guesthouse I stay at is more expensive, but is closer to town, run by a lovely family and has warmer rooms.

The old Ottoman Gorica Quarter of Berat

Most of my stay in Berat is handicapped by ferocious torrents of rain. In fact the rain was so severe across most of the country that whenever I watched the national news it was all total mayhem; monumental floods, overflowing rivers, main highway roads blocked by mud and sludge etc. I was even wondering whether I’d make it on to Tirana on time? The entire second day of my stay in Berat was spent inside my room. When on the third day the rain still hadn’t softened, I was so determined not to spend another day bunkered in my room, I decided to brave the deluge. All I had was my small black umbrella I purchased from a vendor in the Omonia district of Athens for a couple of euros.

Castle walls of the old hilltop Kalaja neighbourhood in Berat

I wanted to visit the old Kalaja neighbourhood located on top of a hill within the walls of the old city castle. It is a quite a shlep to get there and with the lashing rain and low hanging clouds even more challenging. About two thirds of the uphill stone path have turned into rapid streams of water. I invariably step into the steams and my busted Vans are already soaked to the bone. Yet I persevere and make the entrance of the castle walls at the top of the hill. From where I am, all of the town below is smothered in substantial puffs of nimbus clouds.

A cloud smothered view of Berat from the historic hilltop Kalaja neighbourhood

Yet I am glad I made it. The old neighbourhood within the castle walls is a gem of stunning old Ottoman architecture and narrow stone alleys and passages. Walking through this maze evokes mental images of passing though a slice of medieval England with a Turkish twist. It feels very authentic here and this is no museum. It is a living and breathing neighbourhood where locals go about their daily lives.

Photographs from the old Kalaja neighbourhood

What is interesting is that for a long time Kalaja was a Christian neighbourhood and at one point had around 20 churches. Today there are fewer churches, yet the largest church in the district, the Church of the Dormition of St Mary (Kisha Fjetja e Shën Mërisë), is an old church still in existence dating back to 1797 and was constructed on the base of a church from the 10th century. This church is the site of the Onufri Museum. Onufri was a 16th century Orthodox icon painter and Archpriest priest of the Albanian town of Elbasan. He is considered the most significant icon painter of a group of Albanian icon painters from the 16th century who were instrumental in reviving the style of old sacred religious icon painting which flourished during the pre Ottoman Byzantine period. Some of his panel paintings are featured in the museum along with works by other Albanian Iconographical painters made between the 16th and 20th centuries. The enormous and ornate iconostasis situated inside the church is magnificent and one of the finest creations of the 19th century by the very best Albanian wood-carving masters. The iconostasis features two rows of icon paintings created by the ‘Grabovar’ icon painters from the Çetiri (or Katro) family under the leadership of the master icon painter Johan Çetiri. The carving of the iconostasis is documented to have been constructed by two master craftsmen, Masters Andoni and Stefani. It’s prohibited to take photographs but I am so blown away by the works that I sneak a cheeky pic on my Motorola smartphone.

The elaborate gilded 19th century iconostasis inside the Church of The Dormition of St Mary

16th century icon painting on wood by Onufri

Outside the church there is a display of black and white photographs of Berat from the early 20th century. They show scenes of life in the town including a photograph from 1918 of the old Gorica quarter of Berat with its many old Ottoman era houses all grouped together on the side of a hill.

Photograph of the Gorica Quarter from 1918

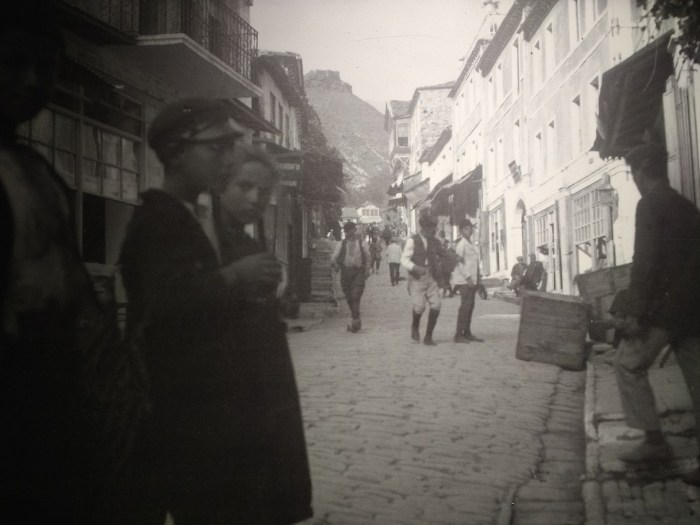

Photograph of the old bazaar from 1908

The rain is still fierce and by the time I return to my guesthouse my shoes, socks and rucksack are soaked. In the evening I have dinner at a local taverna restaurant called Weldor. I’ve already eaten there a few times and I am always served by a cordial young waiter who speaks faultless English. He’s never been to England but for many years he worked in a hostel run by a guy from Newcastle. The restaurant serves delicious and authentic Italian pizza, pasta and risotto dishes made by an Albanian cook who spent many years in Italy working as a chef. The local staples are also excellent and tonight I order a homemade casserole dish made with aubergines and served with some of the finest bread I have ever tasted.

Traditional Albanian cuisine at Wildor restaurant

By the next morning the rain has stopped and there are even some patches of blue in the sky. I seize this morning before I depart to Tirana to walk and explore the town in a way that was long denied to me. The main pedestrian promenade in the centre of town is covered in sludge. Already there are men at work with shovels and hose pipes trying to remove and wash away all the mud. Watching the people at work is like witnessing the aftermath of some natural disaster. I return to my previous guesthouse where I’d left my pyjamas. The owners greet me with a smile and hand me a plastic bag containing them. I tell them I am staying with a friend.

The aftermath of days of heavy rains, which flooded many parts of Albania

I walk over the river to the old Gorica quarter. Most of the cobbled paths are smothered in sludge with huge puddles making walking a challenge. From Gorica, I have a super view of the old town on the other side. Both this district and the old town are full of old classic Ottoman style houses each side mirroring the other and both responsible for this being known as the Town of 1000 windows.

The old town of Berat from the other side of the river

The family at my guesthouse arrange for me to go to Tirana via an acquaintance who will be driving there. I spend the remaining couple of hours of my time in the foyer with the family and their two adorable dogs, Spiky and Lucky, before a silver hatchback Golf pulls up to take me to my next destination.

By Nicholas Peart

©All Rights Reserved