Day One: Mon 25th September 2017

Travelling to Peja

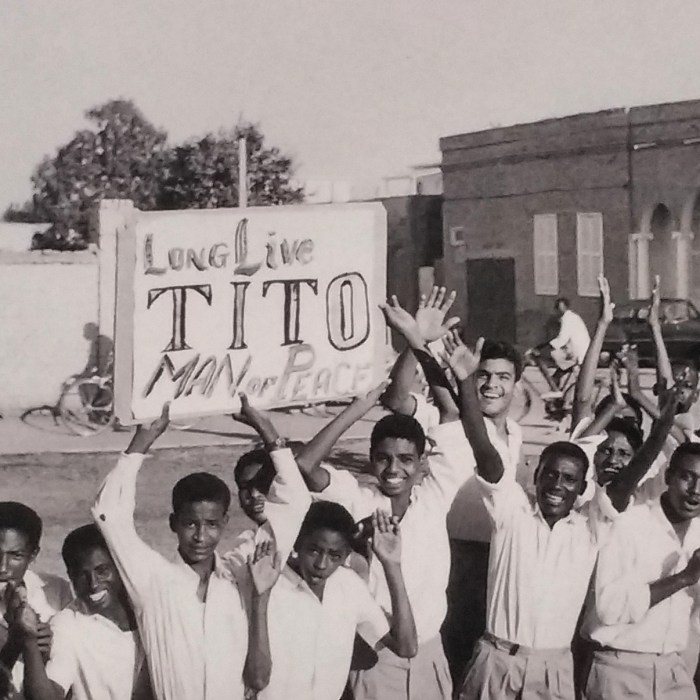

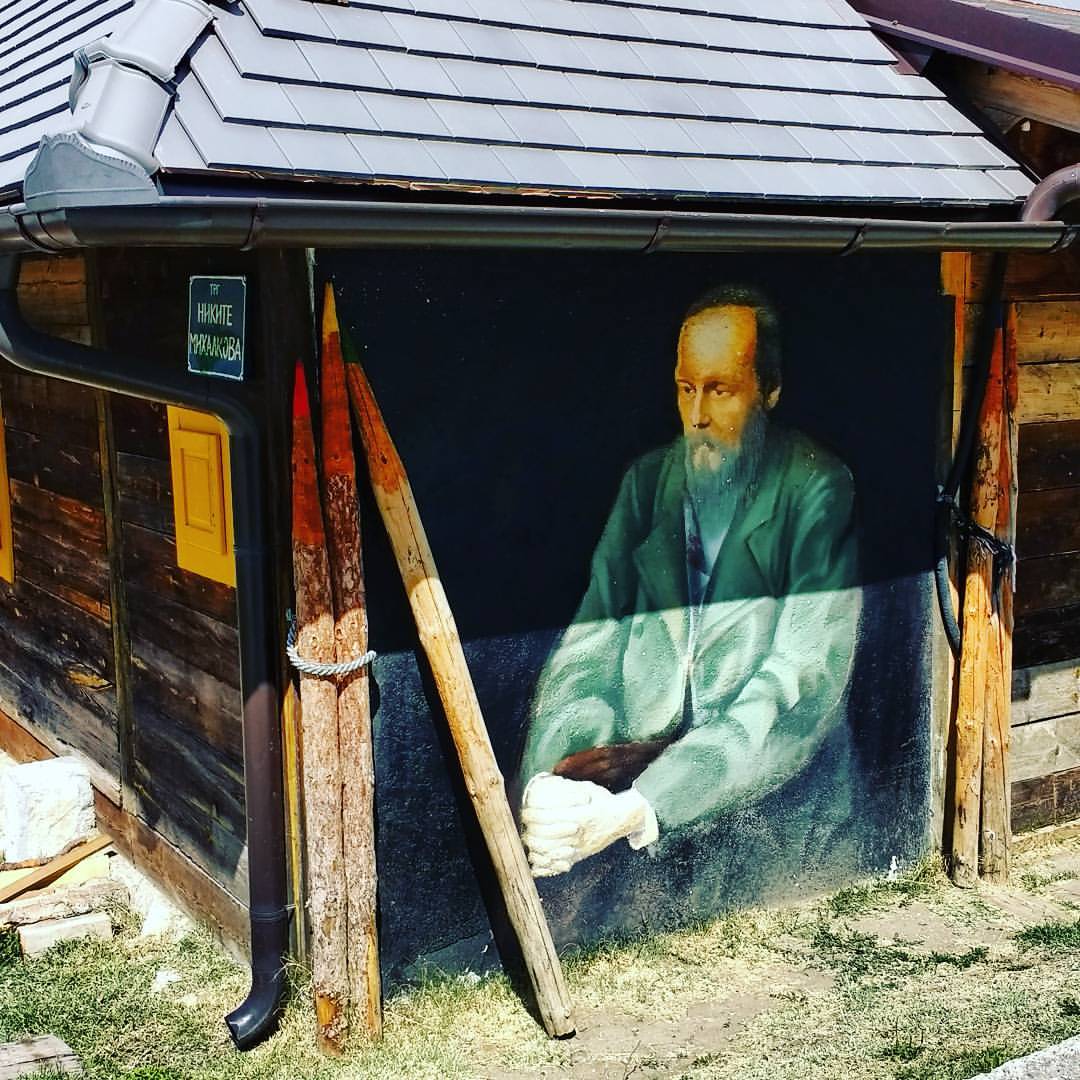

Yesterday I arrived in the provincial Montenegrin mountain town of Berane at 7pm. 12 hours earlier I departed the town of Mostar in Bosnia and Herzegovina for the city of Podgorica, the capital of Montenegro. I get into Pod’, or Titograd as it used to be called at 1.30pm. My connecting bus to Berane departs in two hours. Perhaps I am mistaken but Podgorica is not a pretty place. Knackered Communist era living blocks surround the bus station and even the bus station itself has barely changed since about 1974. I think Titograd is a more fitting name.

I find a modern pizzeria restaurant about 100 metres outside of the bus station from where I take the opportunity to use the bathroom (immaculately clean I could eat my capriccioso pizza off the ceramic floor – yet the lights go off when I am already doing the business) and the free wi-fi to book my accommodation in Berane, and have a good meal that isn’t crisps and chocolate bars. The waiters speak flawless English.

For the duration of the Pod-Berane bus trip, we journey through the Montenegrin countryside; an authentic and unspoilt slice of rural Balkans. When I arrive in Berane the sun is already setting and I realise I have already traversed through most of Montenegro in less than a day. It’s not a big country.

The Montenegrin mountain town of Berane

Berane is not the kind of place you would want to be anchored to for too long; especially if you are young and alive. Not much goes down here and it reminds me of a scoop of time-forgotten Brexitville unceremoniously dumped in the middle of the countryside. There is a bus to the Kosovan town of Peja leaving the following day at 11am. Apart from the hotel receptionist where I am staying, absolutely nobody speaks English in this town. I know perhaps ten words of Serb-Croat with a few more Polski words to boot but that only gets one so far. I soon learn that the 11am bus is delayed by 40 minutes. That’s quite a delay but I refuse to leave this one horse station for fear that I will miss the bus. I constantly keep my eagle eye peeled for the bus. When it arrives it’s one of those retro Communist era buses from about 1981; a far cry from gap yarr Euro Rail travelling. I am the only tourist on the bus. Most of the passengers are Kosovan/Albanian.

When we arrive in Peja three hours later, it is raining hard. I have no map of this city of functioning wi-fi on my phone. I wait at the bus station for the rain to soften. I realise I’ll be waiting a long time. Foolishly, I have no umbrella (I lost my last one somewhere on the Paris metro, I think) and I decide to brave it. As I walk along the main road towards what I think will be the centre of town, I am soon rewarded by the sight of a modern Diner style restaurant. They have wi-fi, much to my delight. Not only that, there’s a decent menu and a front display of delicious deserts; many of which I remember from the historic family run patisserie in Sarajevo called Egipat. A filling plate of shredded chicken kebab with chips, salad, and a generous slice of tiramisu for dessert all comes to just €3.50.

Peja town

I continue walking up the main road. I soon approach a pedestrian square, where a large mid to high range hotel, Hotel Dukagjini, is located, but I am on the lookout for the more modest Hotel Peja. Close to me is an airline travel agency. I enter in the hope that someone there may know the whereabouts the hotel. The attractive and courteous young woman at the desk greets me in perfect English. She isn’t sure where exactly it’s located but she kindly offers to call the hotel and the owner duly meets me at the agency. A stocky white-haired man, perhaps in his late sixties or seventies, arrives and together we walk to the hotel. The hotel is only a couple of blocks away directly facing an enormous future-retro eyesore of a building; like something concocted by the architect of the Barbican tower blocks on acid laced Kool Aid. It is unique in it’s ugliness; the No Retreat No Surrender of global architectural monuments. My hotel is nothing noteworthy but perfectly fine for a couple of nights.

Eyesore or work of art?

I spend the remainder of the rain drenched afternoon and early evening mildly exploring what I can of this city within relatively close proximity to my hotel. In no time I discover a small bazaar like street named “William Wolker” street. William Walker, not to be confused with the clumsy failed wannabe 19th century American conquistador, was the head of the Kosovo Verification Mission, which was a peacekeeping mission established to put an end to the Kosovo War of the late 1990s. Former president Bill Clinton and former US general Wesley Clark also each have a street named after them. As does Tony Blair. Many people view Blair as a “war criminal” owing to his involvement in the 2003 Iraq war, but not the people of Kosovo. Here he is regarded very highly and some families who survived the Kosovo War even went as far as calling their sons ‘Tonibler’. The side of WW street is decorated with a maze of tangled black electricity wires, like its trying the outdo the legendary dishevelled mess of wires found in most of the narrow old bazaar alley ways of Old Delhi, but no matter how hard it may try it will never come close.

In Kosovo Tony Blair is held in very high regard

My meanderings soon lead me to the Peja Arts Gallery featuring a solo exhibition of beautiful paintings by the local Kosovo artist Isa Alimusaj. Sadly the gallery appears to be closed even though all the lights inside are blazing. As much as I want to enter, I cannot find anybody who is in charge. Next to the gallery is a library called the ‘Azem Shkreli” library. I wonder if Azem is related to the controversial American-Albanian multimillionaire “Pharma bro” businessman Martin Shkreli? Although I later discover that Shkreli is quite a common Albanian surname. Not far from my hotel by the river is a statue of Mother Theresa, who was originally from Albania. And nearby is a memorial to four soldiers who died during the Kosovo War. In the evening the temperature plummets. I buy a bottle of water and some pears and retire to my room at the Hotel Peja.

Day Two: Tuesday 26th September 2017

Visiting the Patriachate of Peć and Visoki Dečani monasteries

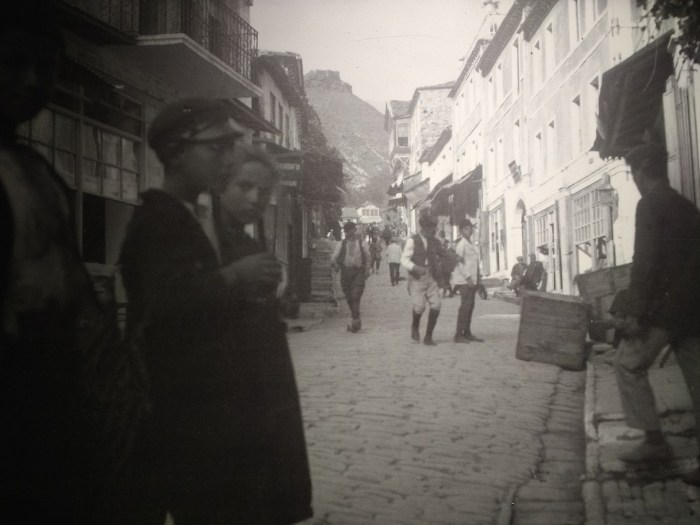

The old Ottoman era bazaar of Peja

Early in the morning I leave my hotel room and walk to the main square where I find a tourist information office. It is staffed by a woman who speaks excellent English. She provides me with a map and highlights all the places I want to visit. My first destination is the city’s old bazaar; like a miniature version of the Baščarsija bazaar in Sarajevo. Walking through the bazaar I try to locate somewhere where I can have breakfast. Ordinarily I skip breakfast, but not this morning. I am so hungry I could burn down cities in return for a large plate of čevapi. I follow my nose, towards the source of the pungent smells radiating from the town’s burek and čevapi eateries. I am led to a čevapi joint called Oebaptore Meti. And what a good call that was. The Cevapi here is as good as it gets in the Balkans. Not only that. I also receive a generous side of salad and grilled vegetables. And all for €2.50. The overpriced pretentious bistros of Paris can do one. The food here is divine. I think Anthony Bourdain would concur.

The best cevapi in Peja

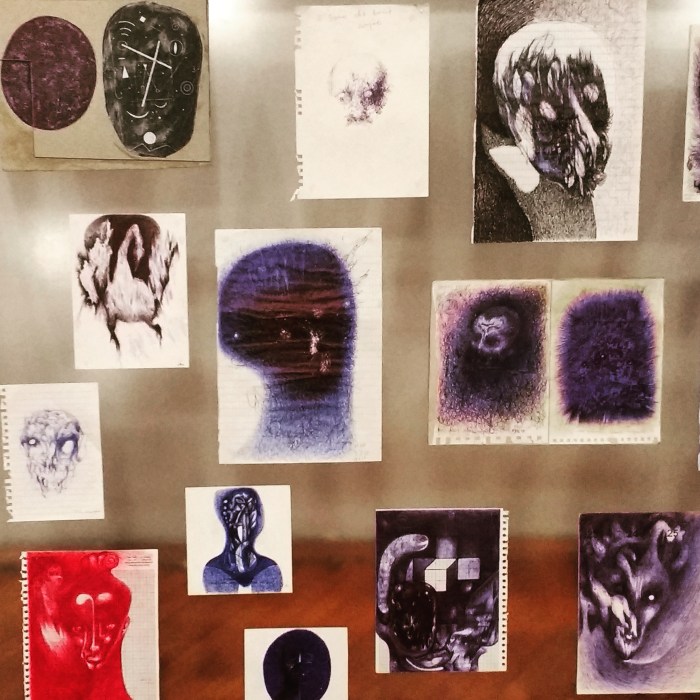

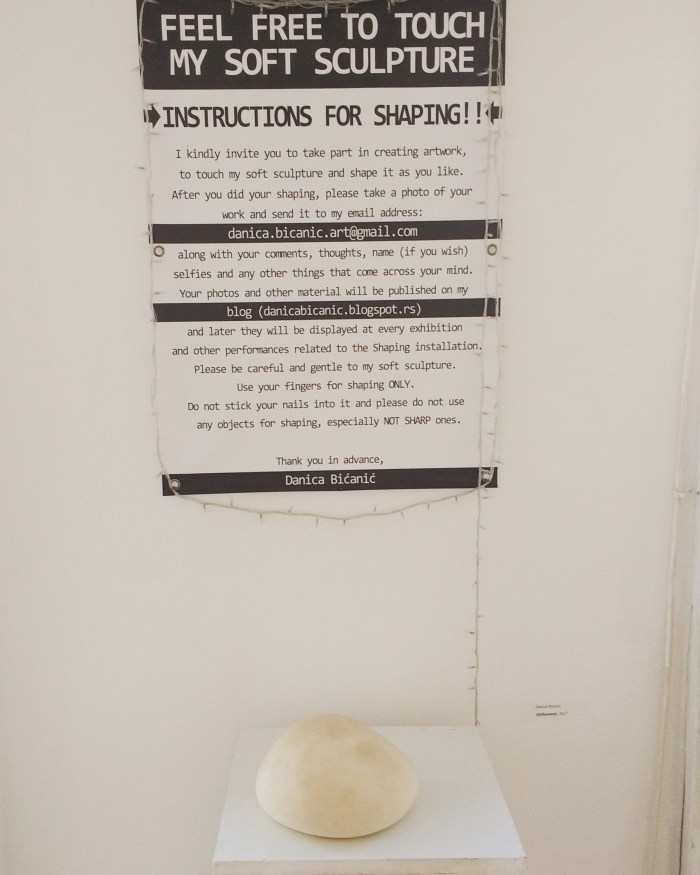

Belly overstuffed and belt loosened, I revisit the Peja Arts Gallery containing all those magical paintings by Isa Alimusaj. Initially I come to the conclusion that the gallery must be closed, but after giving the retro gallery entrance door a firm push, to my delight, I stumble inside. The paintings of Alimusaj are magnificent. Wow! What a privilege it is to discover such a brilliant and gifted artist in the unlikeliest of settings. Those paintings don’t deserve to be hidden in some remote and hard to reach corner of Eastern Europe. They should be on the walls of the Royal Academy of Art. I could reference some well known artists when I look at his paintings; Klimt, Dali, Munch and Bosch perhaps. But the truth is they are like no other artist. Alimusaj is in a league of his own.

Paintings by local Kosovan artist Isa Alimusaj at the Peja Arts Gallery

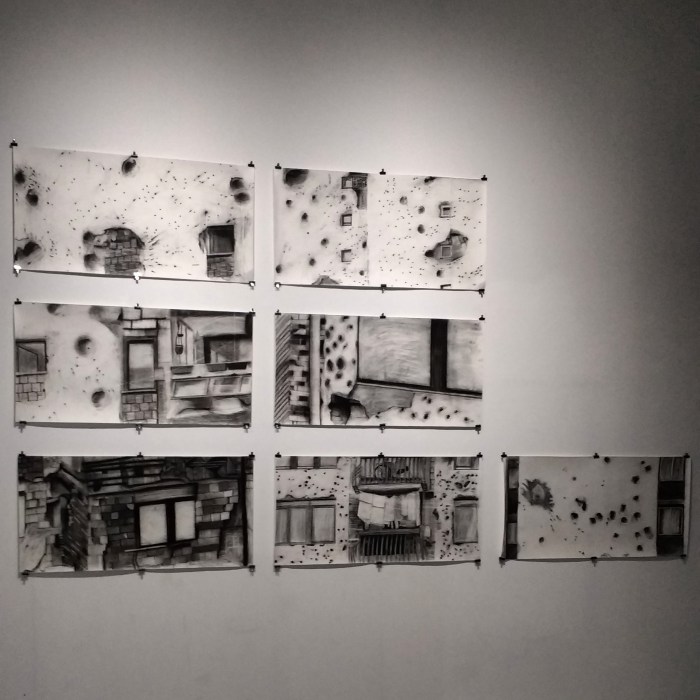

Feeling lifted by seeing such magnificent art, I make the 2-3km walk towards the Patriachate of Pec monastery. As I walk further out of town, I see houses and buildings that were scarred from the war of the late 1990s; destroyed areas covered with newer bricks next to older bricks. The scenery on the walk is beautiful. Even with the sky heavy with low nimbostratus clouds, the mountain countryside sparkles. The entrance to the path leading to the monastery is guarded by NATO’s Kosovo Force (KFOR). At the entrance I show my passport. A group of other visitors soon arrive. A young Englishman called Jack from somewhere in Essex stands out like a whirlwind. He has beautiful long blond curly hair like a youthful Robert Plant and is clad in neo-dandy/hipster ware with shades of his Essex soul brother Russell Brand. He’s with his travelling companion who is an older reserved American who looks like an academic scholar on early Native American history. I get talking with the dude from Essex. They both arrived at the entrance in a battered Mercedes taxi. ‘The taxi geezer charged us 15 euros from the bus station to here. I think he charged us too much’. I think so too. Then apropos of nothing, he points to his reserved travelling companion and blurts out, ‘E’s a West Ham fan too!!’ And here I was thinking, perhaps naively, that I was going to have a quiet uninterrupted trip to this monastery, in a hard to reach little travelled part of Eastern Europe, where I’d have it all to myself. How wrong was I. I like Jack though and he seems to be having a thoroughly great time travelling and seeing awesome things and not allowing himself to be trapped in some depressing-ass road to nowhere job in Basildon or someplace around his neck of the woods.

The Patriarchate of Pec monastery

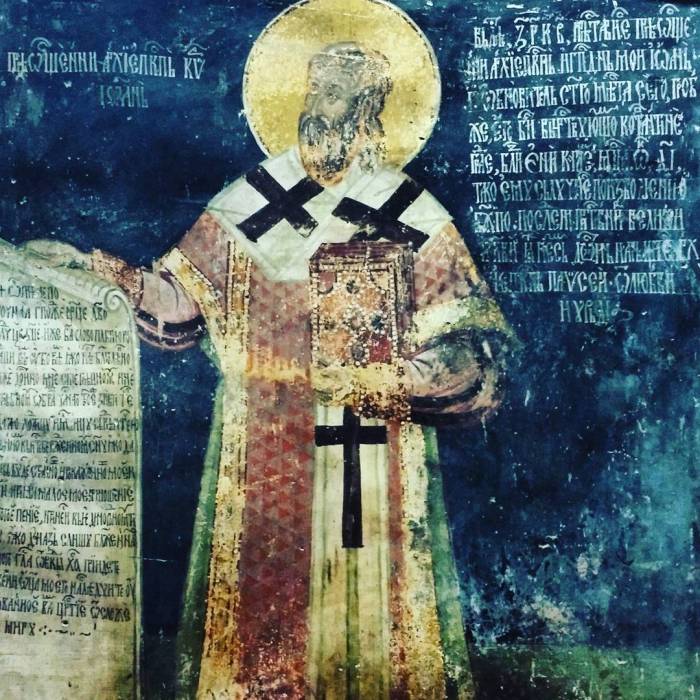

The Orthodox Serbian monastery dating back to the late 13th century is a jewel painting in red-terracotta. Yet it becomes even more spectacular when I enter. What immediately impresses me are the frescos covering all the walls and ceilings; rich, luxurious and brilliant. Its hard to comprehend how after over seven centuries they are still so alive. The extraordinary skill of them is up there with the very best of the early Italian Renaissance painters. I am particularly spellbound by a specific ceiling fresco, which, through centuries of decay, has morphed into a composition that makes even Goya’s most dystopian works look tame. This fresco appears like its engulfed in Mother Nature’s foulest weather and Tesla’s coil violently erupting. I stay at the monastery for a while, marvelling at the frescos before walking back to town.

13th century frescos from the monastery

As I reach Pec town I head towards the bus station to visit another monastery called the Visoki Decani monastery located outside of the town of Decani, which is situated between Pjac and the town of Gjakove. When I arrive at the bus station I have half an hour to kill before my Decani bound bus leaves Peja. So I walk across the main road to a bar and on a whim I order a large cold bottle of Peja beer for only one Euro. Time marches on as I begin to feel the initial effects of tipsiness. Before I know it I have just five minutes remaining. I am no barfly but I drain the remainder of my bottle of beer in a way that would have made Oliver Reed proud. When I get on the bus I indicate to the driver that I want to get off at Decani specifically to see the monastery. Nobody speaks passable English on the bus, but I think the driver gets the message. Forty minutes later as we appear to approach what looks like my destination, the driver signals for me to disembark and points to a road that will lead to the monastery. Decani town seems down at heel and depressed and I don’t think the war was kind to this town. There are memorials to soldiers who died in the war and about ten minutes away on the road back to Pec there is a massive, and I mean gigantic, cemetery, where many citizens who died during the war are buried.

I walk for almost 30 minutes along a quiet country road with lush forests and mountain scenery before I approach the beginning of the entrance to the monastery. This monastery has much more security than the Patriarchate of Pec monastery; its almost as if you are going to a Royal Family wedding. I hand over my passport and rucksack at the entrance before entering the compound. It is a handsome white monastery dating back to 1327 during the reign of the Serbian King Stefan Decanski who was the father of King Dusan who ruled Serbia during the golden age of the Serbian Empire. Yet the monastery has a turbulent history becoming the target of many attacks and attempted attacks. Since the Kosovo war, the monastery has been extremely vulnerable to attacks including an incident on 30th March 2007 when suspected Kosovan Albanian insurgents threw hand grenades at the monastery. Fortunately, not much damage was created. This is one of the reasons why the monastery is under constant tight security.

By the Decani monastery

Like the Patriarchate, the Decani monastery is decorated with monumental frescos. When I enter a procession is already in full swing. The main area of the monastery is exquisite with a sky-high ceiling, elaborate frescos and many tall candles on a suspended chandelier, which one of the orthodox monks would put out one by one with a long metal candle snuffer stick.

Inside the Decani monastery

It has been an awesome and active day today. I am exhausted by the time I return to my room at the Hotel Peja.

Day Three: Tuesday 27th September 2017

Travelling from Peja to Pristina

At midday I check out of my hotel room. The young woman who is in charge arranges a taxi to come and collect me to take me to the bus station from where I will take a bus to the Kosovan capital of Pristina. She is very kind and speaks excellent English. Last night she made me a complimentary mint tea. She tells me that a taxi to the station should not exceed one Euro. I ask her, out of interest, how much a taxi should cost from the station to the Patriarchate monastery? She tells me two euros. I mention my Essex friend paying 15 euros. She looks at me as if he jumped out of a plane without a parachute. As I go to my taxi she insists that I don’t pay more than three euros for a cab from Pristina bus station to the location of my accommodation over there.

The taxi driver is a stocky middle age Kosovan-Albanian with a severe crop. He doesn’t speak a lick of English, but he can speak some German having lived in Germany for 18 months as a refuge during the war. I communicate with him in my fractured German.

Inside Peja bus terminal

At the bus station I locate my knackered old school Pristina bound bus. I nod in and out of consciousness for the duration of the journey. As we approach the outskirts of Pristina my first impressions are not full of joy. Arriving at the rundown bus terminal I begin to feel that the city centre, and more importantly my guesthouse, is no stone’s throw away. I haven’t the faintest notion where I am in relation to the city centre. With no map to guide me and no SIM card in my phone it is going to be challenging. My hopes lift when I get talking with a young man at the information desk in the terminal who speaks reasonable English. He gives me the password for the terminal wi-fi and finally I can take advantage of good ol’ Google Maps. I have already mapped out my journey from the bus station to my accommodation. When I approach two outside taxi drivers they both want at least ten euros to take me to my accommodation which is more than triple what I was advised to pay by the young woman back at Hotel Peja. I walk on. Even with the assistance of Google Maps, I am obstructed by a loud and aggressive dual carriageway with no infrastructure to cross it. No way am I going to cross this death-trap with vehicles driving at out of sight speeds. I swiftly come to the realisation that paying ten euros for a taxi may not be such a bad idea after all. So I approach another taxi driver. This one speaks no English. Nevertheless I show him the address of my accommodation. After looking at the scrap of paper with the address for what seems like an age, he brusquely says, ‘OK!’. When I press him on the taxi fare, he grunts in German, ‘Drei, vier Euro’. Fuckin’ A. Lets go.

Everything goes swimmingly until we approach the district of the city where my accommodation is supposed to be located. It is situated on the edge of a hill overlooking the city centre. After driving aimlessly across multiple narrow streets, the taxi driver stops at a small convenience store to ask for directions to my place. A middle age woman with red curly hair appears. She speaks refreshingly good English and advises me to go to an Italian restaurant located further down the street, which may be able to better assist me. When I tell her that I am from England, she almost gets down on her knees repeatedly telling me, ‘I love England! The war was so terrible and you defended us!’ The taxi driver then proceeds to drop me off at the Italian restaurant, continually apologising in German for his navigation blunders. I tell him not to worry and get out of the cab. At the Italian restaurant, I find a waiter who speaks excellent English yet he has no idea regarding the whereabouts of my accommodation. Happily though he allows me to use the wi-fi in the restaurant. I call my host via WhatsApp telling him where I am. He duly arrives in a black BMW X5 looking like the ring leader of a human trafficking gang. I am absolutely petrified of him. On arrival at the location of my accommodation it appears that I got more than what I expected. Not only do I have my own private room, I have my own mini apartment all to myself with a breath-taking view over Pristina. As I take it all in, he ominously barks, ‘Pay!’. I have a look inside my wallet and discover that I only have six euros. I ask him whether I can pay later? He’s not happy with my response. ‘Ok come with me I drive you to cash machine’. And so I put back on my shoes just as I took them off and we had to his black mafia mobile. He drives me to some BNP Paribas cash machine located outside of the city. As I attempt to withdraw 100 euros, the bank tells me there will be a flat five euro withdrawal fee. So I double my withdrawal amount to 200 euros. When I pay him he becomes less intimidating. The hard as nails Lennie McLean façade morphs into soft as butter Dr Phil. He offers to drive me all the way to the centre of the city.

Pristina at night

My impressions of Pristina become more positive the closer I get to the centre. My quest to find a tourist information centre and a map fails miserably. On a positive note, I ask two random young guys for directions to a city centre based hostel where my chances of finding a city map are high. They are both wonderfully friendly and speak fluent English. At Hostel Hun, located on the forth floor of a building, I meet a young hostel worker who speaks perfect English. He gives me a map of the city. I am not a fan of dormitories, but this hostel is quiet, clean and appears well run. I make a reservation for one night in the six-bed dormitory room for my third night in Pristina.

Afterwards I walk to a nearby diner where I order a combo of chicken and beef kebab meat with chips and salad. I haven’t eaten all day. I am still peckish after finishing my meal and so I order a sandwich with small hamburger-like patties and salad. Then I head back towards my mini apartment. On the way I pause at a modern café/bar and order a slice of the Three Milks cake. It is delicious. Later I amble up the hill back to my pad.

By Nicholas Peart

(c)All Rights Reserved