My time spent in Morocco during the months of November and December last year proved to be quite fruitful overall in my search for old vinyl records in this country. This was my sixth trip to Morocco. I have travelled extensively across the country in the past yet I knew very little about the country’s music and musical history.

In the months before I embarked on this trip I tried to look for old Moroccan music on the internet and even created a YouTube playlist of old Moroccan songs I discovered and found interesting. Via the online vinyl records database site Discogs, I also stumbled upon an interesting and esoteric compilation entitled Kassidat: Raw 45s From Morocco released in 2013 on a small label called Parlortone. I loved the songs on that compilation and began to find out more information on the old major Moroccan record labels such as Boussiphone, Casaphone, Koutoubiaphone, etc, and all the many releases on those kinds of labels. I also discovered some very helpful blog posts written a number of years before my trip by travellers who documented their digging adventures and stories across the country. These blog posts were very helpful and gave me in advance a taste of some of the music and artists to look out for, including some unique Moroccan singers and musicians.

My Moroccan crate digging (mis)adventures begin in the old walled medina of the imperial city of Fez. The medina is a veritable never ending labyrinth of narrow and winding passages. It is an awesome and fascinating place yet it’s equally at times an overwhelming, high pressure and high octane experience. Some of the souk sellers are hardcore in their persistence of persuading you to buy stuff from their shops even if you only project a mild glance.

Deep in the medina I find a small bric-a-brac type shop selling miscellaneous junk shop bits. In the corner of the shop, I spot a small pile of 7 inch records (or 7s as I like to refer to them). The records look exactly like the kind of discs I am looking for and superficially tick all the boxes. Alas, on closer inspection some of the records are in very poor condition. I discover cracks and heavy scratches on the surface of some of the records. Also, I notice that many of the records are not in their correct sleeves. I have no intention of buying any of these records even though the shop owner is insistent on giving me a ‘good price’. I reply with a calm but firm ‘La shukran’ and continue down the endless maze of the medina.

The medina of Fez

In a quiet and more sedate part of the medina, I find a nondescript hole-in-the-wall cafe where I pause for a strong pot of pick-me-up the a la menthe with enough sugar to give me some serious dental decay. If I were a careers advisor in Morocco, I would recommend a career in dentistry as you will always find work! But I digress. This is just what I need right now at this moment in time. This brew sustains me in this can’t-stand-the-heat kitchen of Fez’s medina.

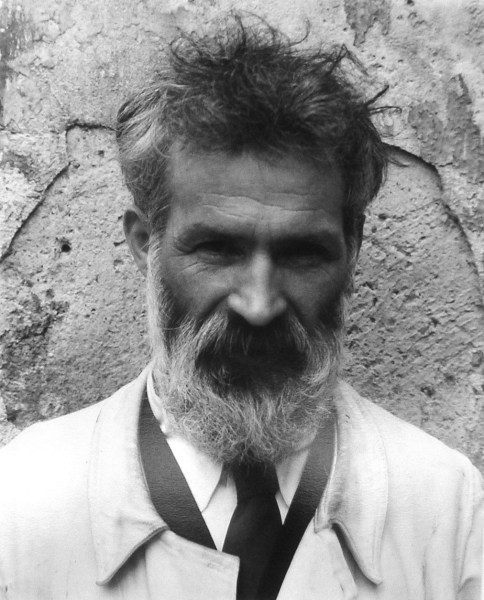

On the way back to my riad accommodation, I stumbled upon a small and cosy antiques shop exuding a laid back old bohemian vibe. An old John Lee Hooker song hums from the back of the shop. Situated amongst the pillars and stacks of trinkets smoking on a pipe is the shop’s owner, Omar, who could be a throwback from 1950s Tangier when the city’s residents included the Beat writers William S Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg. Omar is a dude and refreshingly bereft of the characteristics of many of the grade A hustlers in the medina. In his humble little emporium he has a sizable pile of vintage Moroccan 7 inch records unstably resting upon each other like jagged mini Babel towers. Next to the 7s is a stack of dusty LPs, but it is the 7s that interest me. A lot of the records are in tired condition, but there are a number of records that are not too bad and with some thorough cleaning I could probably restore them to a much better condition. My fundamental rule here is to avoid the records that are severely trashed – regardless of how rare they may be. Any records that are cracked or heavily scratched are a no-no for me. Omar has the records I am looking for. On my initial visit to his shop I purchase two old Moroccan 7s that look interesting and are in good condition. The first record is on the Koutoubiaphone label by Rais Hmad Amentag, a traditional Berber singer and musician. And the other 7 is on the Atlassiphone label by Chaab Mohamad Hilali. I have no idea who either of them are but they look intriguing. Omar wants 40 Dirhams for each record, but we agree on 50 for the two.

For the remainder of my stay in Fez, I make a few more visits to Omar’s shop where I purchase more records. I would say that in total I purchased 10 records from him. I found some crackers in his shop including a couple of 7s on the Boussiphone label by Mohamed El Aroussi, who is a jbala style composer and singer from the Taounata Province, as well as a rare 7 by Albert Suissa, a Moroccan Jewish musician from Casablanca. The Suissa 7 was released on the label, Editions N. Sabbah, which was an old label from Casablanca dating back to the 1950s that released many records by Moroccan Jewish musicians. I know very little about the music of Jewish Morocco, but it was thanks to a blogger called Chris Silver and his excellent and revelatory post, Record Digging, Cassette Collecting and Musical Memory In Jewish Morocco, published in 2012, that I was able to learn a bit about it and it was through this post that I first became aware of Albert Suissa and other notable Moroccan Jewish musicians and singers.

Most people who come to Fez will visit the famous medina, but very few venture to the Mellah, the old Jewish quarter of Fez. Morocco used to have a large Jewish community. Before the state of Israel was established in 1948, around 265,000 Jews lived in Morocco making it the country with the biggest Jewish population in the Muslim world. By 2017, that number had been significantly reduced to only a couple of thousand. When Morocco had a sizable Jewish population, the mellahs in the large cities were thriving. Sadly, as the Jewish population diminished over the years, the mellahs fell into a state of neglect. But the mellah of Fez is not a sleepy part of the city. There are some amazing old buildings, albeit in a crumbling and worn state.

The mellah of Fez

There is an energy here, but thankfully it isn’t of the intense and high stress variety that one finds in the medina. Here nobody bothers you or tries to sell you anything. My random mellah wonderings lead me to a small block of antique shops. The first of these shops that I visit has a small pile of vinyl LPs on the floor near the entrance. I have a hurried flick through them. Sadly none of the LPs are of much interest to me and are mostly European landfill records from the 1970s and 1980s. However, in the next shop I visit I spot a stack of vintage Moroccan 7s on a table at the back. They look promising and I dig out two 7s including a rare 7 by Fatima Zehafa, an old aita singer from the town of Settat, on the Ifriquiaphone label. The shop owner wanted 100 Dirhams for both 7s, but we eventually agreed on 60.

Fez crate digging fruits

From Fez, I take the train to the nearby city of Meknes, only an hour away. I stay at the faded French colonial style Hotel Majestic in the pleasant and rather modern nouvelle ville. In the morning of my second day in Meknes, I have breakfast and then take a petit-taxi to the old walled medina part of the city. The medina of Meknes is big with lots of souks, but it is free of the almost constant hassle of the medina of Fez. Walking deeper into the heart of the medina I soon enter a marche brocante area with lots of stalls selling antiques and other miscellaneous items. One stall displaying a dazzling kaleidoscope-like array of old trinkets and bits catches my eye. The elderly owner has a modest stash of old dusty 7s that I dig through. Unfortunately, many of the records are in a sorry state and when I do find a record in reasonable condition it is not in its correct sleeve.

The medina of Meknes

Meknes doesn’t yield much in my digging searches. Fortunately, I have more luck in Rabat, the capital of Morocco and the next city I visit. In the eastern part of the medina of Rabat towards the end of Rue Souika is the old market of Rabat. Here I discover a number of antique and bric-a-brac shops. The first one I visit is run by a bona fide curmudgeon. He brings over a pile of old 7s. It is not a bad stack at all. It’s a mix of vintage Moroccan records with a smattering of records from Egypt and Lebanon. I pick out a nice looking 7 by the Lebanese singer Fairuz. It is however not a Lebanese pressing but a French pressing. The owner wants 100 Dirhams for the record. When I offer 30 for it, the owner snatches the Fairuz record from my hand and slams it down on a nearby table. I never witnessed Omar behaving like this, but to be honest Omar was likely so stoned most of the time that losing his temper must have been too much effort. Omar is a cool dude. This guy, on the other hand, has some serious unchecked aggression. I think about duly getting the fuck out of his shop. But in no time the shop owner cools down, relaxes his composure and points me to a small tray of records on the ground. On first impressions the records don’t excite me, but the owner tells me that they are 25 Dirhams each. Most of the records in the tray are charity shop 70s Euro Pop fodder destined for the bonfire. I do however get lucky and unearth a vintage Moroccan 7 on the Casaphone label in great condition and an immaculate old Egyptian 7 on the Sono Cairo label in its original company sleeve. 25 Dirhams for each of those records is an excellent price and I don’t even haggle with the owner.

The medina of Rabat

I visit a couple more shops in the old market. Both shops have records, but I don’t find any that interest me. The next day, I return to the old market of Rabat and randomly check out a small bookshop. I ask the owner whether he has any records? ‘Arabic?’ he replies. I nod my head and he brings over a modest stack of 7s in varying degrees of condition. I select six of the better records from the pile. The ones I pick are all in playable condition with their original picture sleeves. Initially, the owner asks for 300 Dirhams for the records. I put my hustle muscle to work and we eventually agree on 130 Dirhams. These finds include a record by the Egyptian musician Abdel Halim Hafez on the Lebanese Voix Du Liban label as well as a record by the Moroccan singer Fathallah Lamghari on the Ifriquiaphone label and another record by an old Moroccan singer and songwriter called Brahim El Alami on the Koutoubiaphone label.

From Rabat I continue on the train along the Atlantic coast to nearby Casablanca. Casablanca is huge and a grittier city than Rabat. In contrast to Casablanca, I found Rabat a more relaxed and accessible city. Fortunately, Casablanca has a modern tram system and I am able to reach my hotel without too much bother from Casa Voyageurs train station. From reading the aforementioned Record Digging, Cassette Collecting and Musical Memory In Jewish Morocco blog post by Chris Silver, I learn about two record shops located in Casablanca, which I am excited to visit. The first record shop, Le Comptoir Marocain de Distribution de Disques, looks encouraging. It is located only a few streets away from the Hotel Astrid where I am staying. When I finally reach the shop it looks permanently defunct. I later learn the sad news from the owner of a nearby shop that the shop closed down during the COVID pandemic. And much to my dismay again, the second record shop, Disques Gam, also appears to have ceased trading.

Downtown Casablanca

Casablanca is a spicy city. It is the commerce capital of Morocco and for that reason it is not so reliant on tourism like Marrakech is, for example. I love exploring the streets of Casablanca. There are some amazing old faded French colonial era buildings in the centre of the city. When I walk along the streets close to my hotel I feel as if I could be in Marsaille or the Riquier district of Nice. Yet on the fringes of the city’s enormous old medina I know very well that I am in Africa. The old medina surprisingly disappoints in my search for old records. Casablanca hasn’t delivered the goods. However, one day when I am walking along one of the Parisian style arcade streets close to the Place Mohammed V, I spot a stall selling old records. There is a large pile of LPs on the round along with a few 7s. Most of the LPs are no great shakes, but I do find an original UK edition of the second album by Terry Reid – an English musician from the 1960s-70s, also known for turning down an offer by Jimmy Page to be the singer for his new band Led Zeppelin. The vinyl is in respectable condition, but the sleeve is completely destroyed. The 7s are a different story. I find three 7s that interest me. One of the 7s is a rare Algerian pressing. Sadly, on closer inspection of the vinyl I detect a crack on the surface of the vinyl and end up passing on it. The second record is by an old Moroccan Jewish musician called Haim Botbol released on the Boussiphone label. I later discover that the Botbol record is also quite rare. The third record is by an old Berber musician on the La Voix Du Maghreb label. The record seller is very pleasant and is happy to accept 60 Dirhams for both the Botbol record and the record released on the La Voix Du Maghreb label.

Place Mohammed V in Casablanca

On my penultimate day in Casablanca I visit the Derb Ghallef market en route to the Museum Of Moroccan Judaism. Derb Ghallef is raw. Located south of the centre of the city, it isn’t for the faint of heart but I recommend a visit for those who want to experience a taste of rough and tumble Casablanca. The markets sells lots of electronic goods as well as furniture and building parts. When I visit I find a couple of antique shops, but alas no luck in finding any old Moroccan records.

From Casablanca, I take the train further south down to Marrakech. Marrakech, one would think, with its abundance of souks in the old medina would be a mecca for crate diggers. Unfortunately, during my stay here this has not proven to be the case at all. That is not to say that there is an absence of places to find records. There are, but I encounter hurdles. The first shop I visit, close to the large Jemaa El Fna square in the medina of Marrakech, sells an assortment of traditional musical instruments. When I discover a small stash of 7s, I have a brisk plough through them and select a few that interest me. The young owner of the shop is a stubborn and temperamental sod and refuses to accept less than 100 Dirhams a record. This is madness as the records are not uber rare and I personally wouldn’t pay more than 30 Dirhams for each one.

The Jemaa El Fna in Marrakech

At another shop I visit in the medina, I ask the owner whether he has any magic Moroccan 7s? He tells me that there is a record shop only a few shops away and that he will take me there. We end up walking for close to ten minutes and, being rather asleep at the wheel here, it dawns on me that I will have to give this guy some form of baksheesh. When we arrive at the record shop he becomes grumpy and predictably demands payment. I hand him a few coins and thankfully he leaves. I have to admit I am underwhelmed by this record shop. Many of the records are in an irrevocably fucked state. He has an original LP by the Egyptian singer Umm Kulthum. Both sides of the vinyl look like the surface of the moon. The owner wants 300 Dirhams for the record, which is a preposterous price. When I put the vinyl on the shop’s record player, it skips all over the place and fails to play properly. The owner remarks that the reason for this is nothing to do with the fact that the record is totally mutilated, but rather because ‘the record player is no good’. After this incident, I come to the conclusion that the main Marrakech medina around the Jemaa El Fna square is not the place for crate digging. And this suits me fine as I find the whole experience of being in this place for too long like being in a medieval free-for-all open prison. I can’t breathe.

But I don’t give up entirely on Marrakech. At a small shop by a rank of grand taxis outside of the medina, the kind owner recommended that I visit a market on the northern outskirts of the medina called Souk El Khemis. A small local bus departing from close to the Jemaa El Fna takes me to this part of the old town in around 20 minutes. The market here is different to the souks around the Jemaa El Fna. Here, there are no other tourists and nobody bothers me. The souks here sell mostly household goods. There is a souk selling large ornate old wooden doors. Another souk sells bed frames and mattresses and others sell mechanical parts and a variety of secondhand home products. The bit of the market that interests me is the souk full of bric-a-brac shops. The first of these shops I enter sells lots of old books and miscellaneous antiques. In the back corner of the shop I find a cardboard box containing a stack of LPs. Most of the LPs are not what I am looking for and I sadly don’t find any old Moroccan LPs. However, I do unearth an original LP from the 70s on the EMI Egypt label by the Egyptian singer and composer Mohamed Abdel Wahab. The sleeve is slightly worn around the edges, but the vinyl is in stunningly pristine condition. I can’t detect a single blemish on either side of the record. What’s more, the owner lets me have the record for only 50 Dirhams. In an adjacent shop I found a 7 in respectable condition with its original picture sleeve by the Syrian-Egyptian singer Farid Al-Atrash released on the Moroccan Casaphone label. The pleasant and easy going owner is happy to accept 30 Dirhams for it.

From El Khemis, I walk a few kilometres on the road leading to Bab Doukkala at the edge of the medina. There are lots of informal sellers selling all kinds of random items and bits of junk. At one point I see a landslide of miscellaneous crap strewn across the side of the road – like a kind of odd homage to Kurt Schwitters.

Outskirts of the medina of Marrakech

After Marrakech, my Moroccan travels take me to Essaouira, Agadir, Tiznit, Sidi Ifni and Taroudant. I find a few more vinyl bits in these places, but all in all I would say that the cities of Fez and Rabat have been the most rewarding for digging. In the attractive coastal town of Essaouira, I visited a shop close to the main square that appeared to be owned by an elderly French chap. The shop sold many old books and a few racks of old records. He had a fantastic collection of old Moroccan records – one of the best I’ve seen on this trip. Unfortunately, as wonderful as the records were, I found the prices a bit too high for my liking.

I find a smattering of old Moroccan records in the souks of the medinas of Taroudant and Tiznit. In the coastal city of Agadir, I visited the Souk El Had – one of the largest souks in Morocco. Sadly, records are quite thin on the ground here, but I do find a small shop with a modest collection of 7s. From this pile I dug out two interesting old Moroccan records on the Casaphone label. I managed to get them both for 50 Dirhams. The record digging highlight of Agadir for me though is a cool little record shop located not too far away from the market called Records Zaman run by a pleasant young man called Amine. It was founded back in 1967. The shop may be small, but there are quite a number of records to dig through. There are a few rare original Moroccan LPs on the display racks on the walls, but alas they are out of my price range. I dig through a crate of LPs that are mainly western Rock and Pop albums. The crate that does interest me contains a couple of rows of old Moroccan 7s. Whilst digging through them I pull out an old record on the Editions N. Sabbah label by the Jewish Moroccan singer Feliz El Maghrebi. Save for a slight edge warp, the record and picture sleeve are in near perfect condition and Amine lets me have it for a good price. I must have spent a good hour chatting with Amine. He is great company. His English is very good and he shows me his own personal collection of LPs containing some very rare and obscure records across the Arabic world. Amine has a deep love of music and I feel that with him at the helm, Records Zaman will become an increasingly popular record shop to visit. I wish him all the best.

Text and photos by Nicholas Peart

8th February 2024

© All Rights Reserved

LINKS/FURTHER READING:

https://jewishmorocco.blogspot.com/2012/11/record-digging-cassette-collecting-and.html

https://terminal313.net/2016/04/feature-dusty-vinyl-from-rabat.html

Constantin Brancusi

Constantin Brancusi